We’re at the end of the year. No great movies or T.V. shows remain to be seen. The Sox came as close as they’re going to get to the World Series for the next couple years. The Patriots did remarkably well at football, surprisingly, and the Giants did bad at football, but with the usual dash of hope in the form of an electric running back and quarterback.

Here are some of the things that stood out to me as a consumer of sports:

Boston Celtics: last year was disappointing. The injury of Jayson Tatum put a halt to hopes of repeating as NBA champs, and also dented the team’s odds of a successful postseason this year. I can’t say the team was particularly exciting to watch at their best. Something like the Golden Age of the Spurs. But watching wins is never a bad experience. This season I’m taking a break, and waiting until next season to plug back in. Might have to check out Bruins hockey.

Boston Red Sox: Dealing Devers wasn’t a terrible move, in retrospect, but letting Walker Buehler go was. I don’t think the Red Sox could’ve gotten past the Blue Jays this year. But his intensity and power in the postseason would’ve been useful, as would his presence in the clubhouse. That’s the sort of guy Buehler is on a team. A sparkplug, a firestarter. After he left, Bregman was never quite the same. Buehler pitched well against the Yankees and he might have been able to nudge the Sox into the first round against the Blue Jays (where the Sox, instead of the Yankees, would have gotten thumped out). I’m not sure what that portends for next season. A healthy club could probably make the playoffs again. Will the Sox get far there if they make it in ‘26? I don’t think so, not without a little more hitting and a little more pitching.

Having said that, this Sox team was one of the more fun to watch over the past decade. They showed flashes of brilliance, as during a midseason run where they rattled off a couple significant win streaks. They were dismissed with difficulty by a fine Yankees squad — who then got hurried out of the playoffs by a dominant Blue Jays squad — and I’m hopeful the Sox can find a way to build on the pieces they have now. They need everything they had this season, plus one more Crochet-level pitcher (easier said than done) and one more hitter on top of a healthy Anthony and re-signed Bregman (much easier said than done). I’m not optimistic about 2026.

And some of the movies and shows I watched that I either enjoyed, or which I think you can probably skip (in my opinion):

The Terror: An incredibly-cast and beautifully rendered fictional t.v. horror serial that walks the line between natural and supernatural following the crews of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, two British warships that were kitted out to explore the Arctic and look for a passage through the ice in the mid-19th century — unfortunately for them, during some of the coldest years on record. The historical Erebus and Terror disappeared with all hands lost; in this telling, either a monster or a relic population of cave bears (depending on your capacity to suspend disbelief) were responsible, plaguing and killing the crew once the ships become stuck in pack ice. Had me engrossed from the first to last episode, with very little filler.

Severance: Smarter people have already written about this show; all I’ll add to the discussion is a ringing endorsement to watch this if you subscribe to Apple TV. I don’t remember the last time I cared as much about characters as I did watching this program. It’s an incredible show, a marvelous experience, and you don’t get cheated entering into that world. It’s worthwhile.

Bosch: Legacy Season 3: Friends have heard me talk at length about the original Bosch series, which I really enjoyed. Each episode of Bosch seasons 1-4 (and maybe more) is a joy to watch — one never feels lectured to or manipulated as a viewer — one’s time as an audience member is not taken for granted. That wandered in later seasons, and very much so in Bosch: Legacy, both of the first two seasons of which were not the most enjoyable views. Much of the enjoyment I got watching Legacy was owing to the residual goodwill built up by those excellent initial seasons of Bosch.

Season 3 was a return to Bosch’s earlier form. Each episode was satisfying in its own right, while credibly building that most powerful of Boschian narratives: has Bosch gone too far? Is his moral code antiquated or even beyond gray — has he wandered into irredeemable evil territory? Hint: everyone who has ever bet against Bosch has lost money. Watching the series sell and then rug-pull a compromised or flawed Bosch gets me every time. Really enjoyed this unfortunately ultimate season of Bosch, and Titus Welliver’s exceptional acting (has anyone done a better job of inhabiting a role? As good, certainly. Better, I think not).

Reacher Season 3: The first two seasons were very enjoyable. Very good, bordering on great. This season was a disappointment in so many ways. Whereas in the past Reacher’s feats, while farfetched, felt somehow plausible, this season was filled with absurd and improbable moments that didn’t stretch credulity so much as violate it. If one had in the past been able to suspend disbelief due to good acting and better plotting, this season misfired on both accounts. The characters who were supposed to be sympathetic weren’t. The pacing was off. Even the villains didn’t bite as hard, in spite of an all-out effort to make them. I’d pass on this.

Foundation Season 3: A solid ending to an enjoyable series, particularly if you enjoy Sci Fi and never read the original Asimov trilogy (as I haven’t). Two of the last three episodes — eight and nine — deliver an extraordinary payoff, one of the very best in the series. The final episode, on the other hand, was so wandering and worked so hard to tie everything up neatly that I barely remember it. It’s rare that an ultimate episode is overshadowed by the episode before, but that’s what happened here. This was also one of the few series for which I always watch the opening song — like Mad Men and The Sopranos, it helps set the stage for the episode that’s about to unfold. Recommend!

The Last of Us Season 2: Didn’t enjoy this. I’m told it followed the video game faithfully. I watched the first game played, and not the second — didn’t play either — and watched as much of Season 2 as I did out of loyalty both to the game and to the first season.

Cinema, theater, and literature have always been lightning rods for culture war. Years ago I took some heat for saying I didn’t enjoy the most recent Star Wars trilogy, and imagine I might take some heat for saying I didn’t enjoy this season of The Last of Us. My opposition to Star Wars episodes 7-9 wasn’t opposition so much as I simply didn’t enjoy it; the plot was incoherent, and the decision to complicate Luke Skywalker the way the director did seemed arbitrary and not worth the payoff. I think as a writer or a showrunner if you’re going to bedevil a character, a hero no less, you owe it to that character to give them some form of redemption.

And so it was that the second season of The Last of Us was probably doomed by the video game — spoiler alert, one of the primary protagonists from season one is brutally and bloodily murdered in the first episode of season two. The murder, which does not seem suitable for television (frankly) is ostensibly complicated by the fact that it is seen as an act of vengeance by the daughter of a doctor who is killed at the end of season one, by the same protagonist who gets murdered.

As an allegory about vengeance, I’m sure the seasons both work well. But as storytelling it doesn’t; when I see a beloved albeit complicated hero (he kills the doctor who is about to kill the second protagonist, who becomes the hero of the second season) savagely tortured to death, I don’t think “hmm, life is complex,” I think about the very real brutality meted out today by various invading and occupying countries against minority groups or peoples. I think about the absence of justice, the impossibility of justice.

Movies and books and plays are not spaces to muse on the impossibility of justice — because to claim that justice is impossible is a cynical and self-defeating idea. Art is a fantastical space in which we get to see heroic and upright behavior — perhaps with struggle, with complication, with challenge and difficulty, to be overcome — fantasies in which justice is accessible. Because the world we live in, the real world, is a deeply unjust place.

There are other problems with The Last of Us Season 2. I watched the season to the end. It ends up being a kind of torture. I don’t recommend it, because of its sacrilegious and inhumane treatment of Joel and other characters. Game of Thrones got all the “violence and grit for the sake of violence and grit” out of my system. Just can’t watch stuff like that any more.

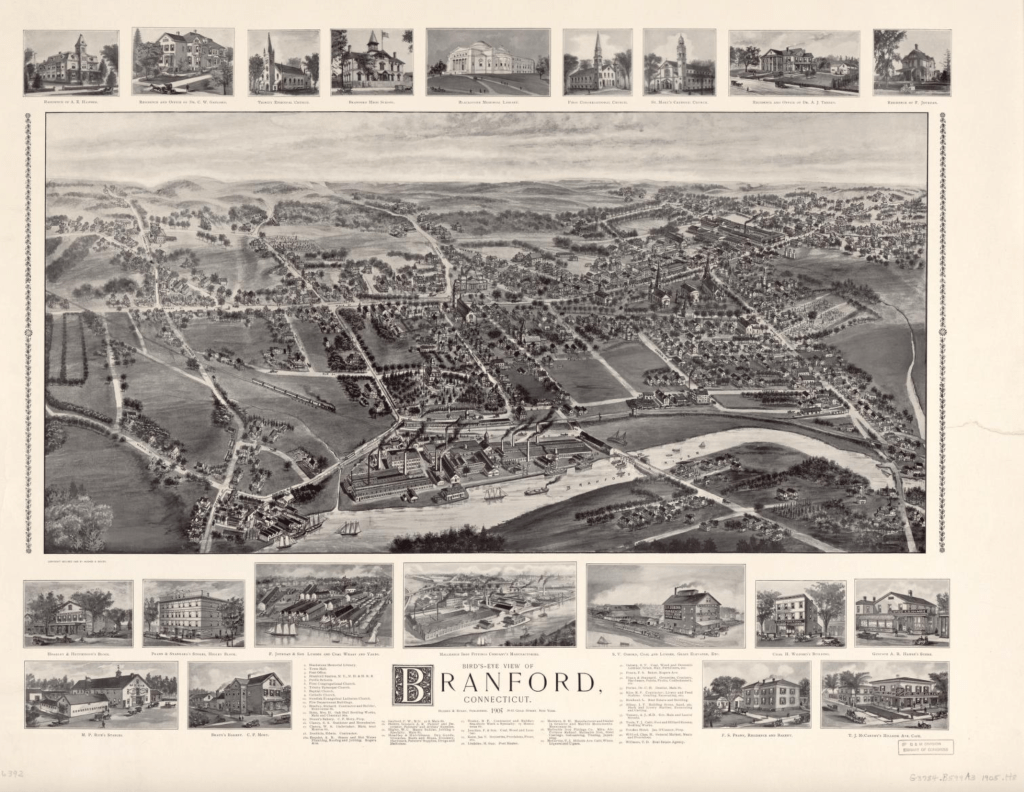

Of literature I read little, and journalism I read quite a bit. The only literature I read this year were stories and books I’d missed by Philip K. Dick (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep), by Stanislaw Lem (Imaginary Magnitude), and some rereading of Hemingway and Carver; the remainder of my reading was tied up with Albion’s Seed and various legal documents relating to Connecticut’s Constitution and General Statutes, so as to become smarter about the state I live in. I tied up my service to Branford’s RTM, as I wrote in another post, and having helped contribute to the law of my town with several ordinances, I was interested in learning a bit more about the context in which those laws were created. It’s interesting. It does feel at times that the code of a state or a country ought to be simple enough that a citizen should be able to understand it before graduating high school; my feeling, reading Connecticut’s state laws, is that they require a lawyer to navigate. While the process by which we have arrived at our laws, statutes, rules, and ordinances as a state has certainly been democratic, what exists today is not egalitarian, and probably a violation of the principles on which the state (and nation) were founded.

For journalism, I read The Wall Street Journal every day. On the day (December 18) I was to choose between continuing my subscription or not, I elected not to; $50 a week for what feels increasingly like banal stories about American culture — the sort of thing I remember reading in The New York Times when I was in high school — was too rich for my blood. This year I’ll likely pick up a subscription to Bloomberg or to Financial Times, I haven’t decided which.

Final recommendation for 2026: avoid this snack at all costs unless you have superhuman powers of self control.